A review of the evolution of feminist thought helps us imagine what the future of #MeToo can look like

Historical feminist thought has been developing its focus for the past several centuries, dealing with issues of biological sex, gender expression, and sexuality. Now contemporary feminists have a solid theoretical platform to expand our understandings of sex, gender, and identity in more nuanced ways. Early feminists set the foundation by denouncing arbitrary distinctions of biological sex in systems of power; following this example, contemporary theorists can zero in on other arbitrary distinctions and pursue the destruction of systemic othering of all identities.

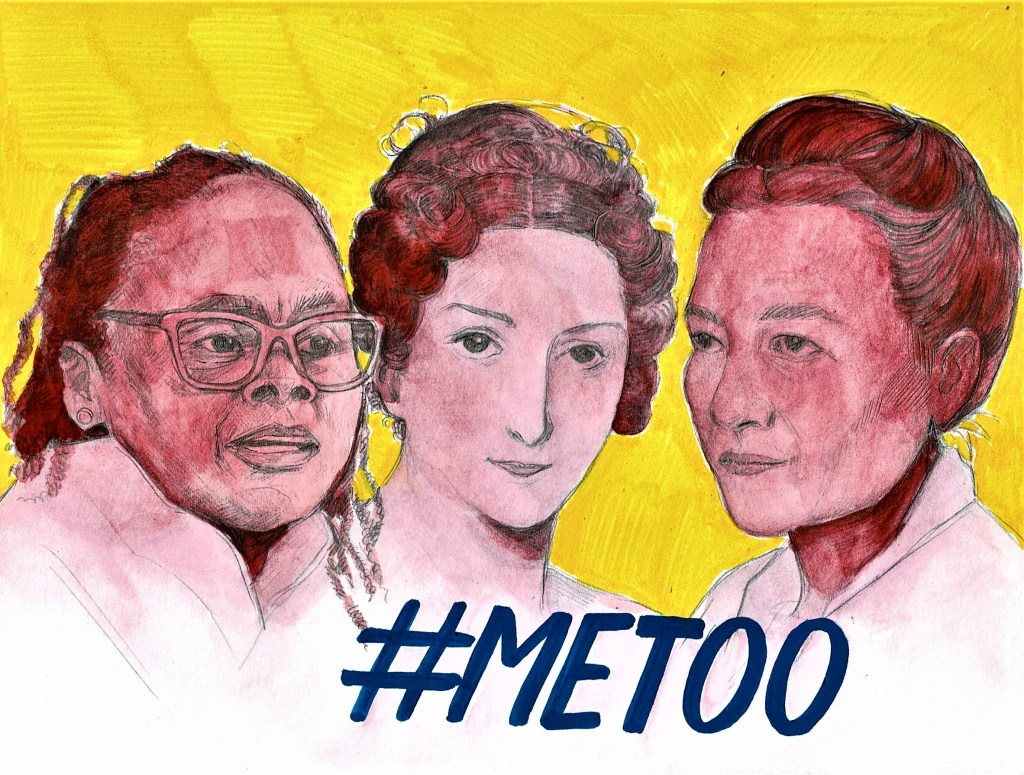

Contemporary theorist Angela Onwuachi-Willig develops a theory of sexual harassment and argues for a reasonable person standard that does not erase identities like race and sexuality in “What About #UsToo?: The Invisibility of Race in the #MeToo Movement.” I argue that this theory is founded on some of the conclusions put forward by both Harriet Taylor Mill in her historical essay on marriage and divorce, and Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex. The dismantling of naturalist arguments for sex-based oppression by Taylor and Beauvoir paves the way for Onwuachi-Willig to discuss how the intersection of sex and race plays into socially-constructed hierarchies which #MeToo has failed to address.

The role of sex in Taylor and Beauvoir’s arguments establish a baseline attack on social constructs masquerading as natural divisions, which is an argument Onwuachi-Willig brings into the modern workplace. Taylor argues against naturalism when she points out differences in child-rearing between the sexes as social constructs attributed by men to women’s natures which then translate to inequity in marriage and the family. Beauvoir compounds on this by theorizing that these social hierarchies necessarily make women Other and unhuman, which cognitively normalizes their oppression by defining them by their biological sex. According to Beauvoir, othering women in this duality has erased from male perception an explicit social hierarchy, creating abstract equality in which any inconsistencies between the agency of the sexes is wrongly attributed to nature. Beauvoir sets a stone for future discourse on the need for intersectionality as well, when she explains that methods normally used to overcome oppression of race or class are not precedents for overcoming sexual oppression, as sex-based discrimination is unlike any other oppression.

The racial erasure in #MeToo that Onwuachi-Willig denounces is a result of feminist methodology that only fits the de-raced male/female duality, where experiences of women of color are ignored.

Contemporaries like Onwuachi-Willig take differences Beauvoir establishes in these power hierarchies and call for intersectionality, a means for dealing with the oppression of those whose identities bridge the dualities. The racial erasure in #MeToo that Onwuachi-Willig denounces is a result of feminist methodology that only fits the de-raced male/female duality, where experiences of women of color are ignored. Thus, Onwuachi-Willig rejects the adoption of a reasonable woman standard in harassment law, as this does not account for race, sexuality, or even gender identity. As #MeToo should be concerned with dismantling societal structures that perpetuate harassment and sexual violence, Onwuachi-Willig’s intersectional critique of these social constructs supports the conclusion that the movement has failed in its feminist objective, and she gets a foundation for her critique from the anti-naturalism stances of Taylor and Beauvoir.

Onwuachi-Willig’s gender politics in dealing with this deficiency in #MeToo are also well-informed by the foundations laid by the evolution of thought between Taylor and Beauvoir. When Taylor addresses social constructs that inform differences between biological sexes, like timidity and dependence she lays the groundwork for Beauvoir, who attacks dualities of sex and socially-constructed femininity and masculinity. Society, Beauvoir posits, uses the pseudo-natural differences of sex to produce the standards of the femininity/masculinity duality. She notes sexuality as another human construct forced into a dichotomy of male sexual domination and female frigidity; another form of sex-based oppression, the sexualization of women, evolves from this new dichotomy. Addressing sexualization creates the foundation for contemporaries like Onwuachi-Willig to dissect female sexuality, another social construct, and how it intersects with racial stereotypes; both are created in manners that enforce alterity of female, non-white identities.

From such evolution of discourse, feminist theory arrives at these focal points of sex, race, and justice which drive modern movements like #MeToo.

Perhaps most importantly, historical recognition of the harm of sexualization by Beauvoir has allowed contemporaries like Onwuachi-Willig to establish its causal relationship with sexual violence; black women, for example, are frequent victims of sexualized violence by police due to the vulnerability of their credibility against stereotypes of hypersexuality and criminal behavior. From such evolution of discourse, feminist theory arrives at these focal points of sex, race, and justice which drive modern movements like #MeToo.

Onwuachi-Willig’s treatment of biological sex as an identity that is vulnerable under certain power structures, like Beauvoir’s dualities, leads Onwuachi-Willig to produce the reasonable person standard that accounts for the difficulty that different individuals may face due to their race, class, and sexual orientation. These difficulties include damaging stereotypes about the sexuality of different sexes, races, and socio-economic groups and sex-based and sexualized violence, which is in part founded on the tie Beauvoir makes between sexual activity and power in the dehumanization of women. In fact, Onwuachi-Willig’s focus on the workplace applies Beauvoir’s Independent Woman concept to modernity, acknowledging the significance of sex in one’s holistic identity, and how the sacrifice of it to rid oneself of alterity is an egregious loss, even if the alternative is forced confinement in Otherness; this spurs on the contemporary feminist movement to create a workplace where this sacrifice is unnecessary.

By studying these historical feminist foundations of Taylor and Beauvoir, a more comprehensive understanding of the modern theory of Onwuachi-Willig arises. Onwuachi-Willig’s theory of ending sexual harassment, and future theories that will inevitably build on hers, can hopefully help us build a #MeToo movement that includes all of us.

Illustration: Alyssa Sliwa is an illustrator for F-Word magazine. She is currently undecided on a major and minoring in the Fine Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania.

Leave a comment